“WHALES!!!”

“ORCAS!!!”

“WHALES!!!”

Giovannina was shouting as she ran in her flip flops along the rocky edge of Jones Island. We had been packing up after a lovely breakfast with Gretchen, Noel and Odin when, seemingly out of nowhere, there were two orcas, an adult female and smaller calf, cruising less than fifty feet from the shore. They were swimming north past our campsite, hugging the coastline, moving at a steady, not-a-care-in-the-world pace. On land it was a different story. As soon as Giovannina started shouting, everyone within earshot sprung to their feet and began running in the direction of the hullabaloo. Unfortunately, our gangly two legs are no match for the powerful fluke of the Blackfish and within a few minutes, the two orcas had moved well past the next point and were out of view. This was the second time we had seen orcas from Jones Island, the first being eleven years earlier during the first kayak trip I did with Giovannina.

But these two whales weren’t resident orcas. No, I’m pretty sure they were transient orcas, also known as Bigg’s Orcas, named for Michael Bigg, the Canadian Researcher who spent most of his life studying killer whales along the B.C. coast. While I appreciate honoring Dr. Bigg by naming this group of whales after him, I still prefer to think of these whales as transients because, unlike resident orcas that feed on salmon and so tend to congregate (or reside) around salmon runs, transient orcas feed on marine mammals, like harbor seals, which are more widely dispersed than salmon. Consequently, transient orcas tend to wander from place to place looking for big, fatty seals, sea lions and even large baleen whales to feed on. Then again, as I just explained, the residents are having to wander more and more to get their food as well these days, so maybe the resident vs. transient distinction isn’t as appropriate as it used to be. Regardless, it was absolutely awesome to see a couple of whales swimming right past our campsite. And a mother and calf, no less! It was quite an auspicious start to a day of paddling.

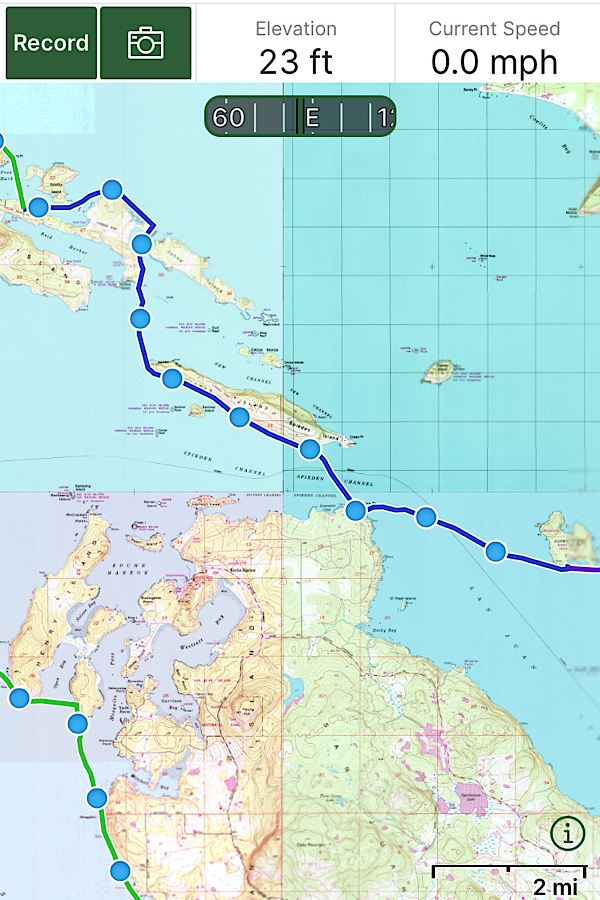

Currents in our favor, we easily made our way along the length of Spieden, passing Sentinel Island, the “gumdrop” island made famous in the book Living High, written by the homesteaders Farrar and June Burn. I still can’t believe the Burns, using only a row boat, made a home on this forested rock surrounded by ice cold water and vicious currents exceeding six knots. As far as we could see, Sentinel Island provides no safe landing beaches and has near-vertical cliffs on all sides. I guess the reward of having their own island must have been enough to endure all the hardships that came with living there.

At the western tip of Spieden, we turned north, making our way to Stuart Island via John’s pass. We could’ve headed west to Reid Harbor, but I’ve always preferred camping at Prevost Harbor on Stuart’s north side. Both harbors are natural safe havens, providing relief from storms in almost any direction, and so they can be quite crowded with motorboats on a summer weekend. For a kayaker, this means trying to sleep in your tent while someone blasts classic rock songs from their cockpits late into the evening. When I was a guide, Reid Harbor was our preferred campground for clients because it was a shorter paddle from San Juan Island. Prevost Harbor took longer to get to, but was typically less crowded. With Covid enforced social distancing in full effect anyone with a boat was out on the water, many using laptops and cellular hotspots to turn their cabin cruisers into floating offices. I knew that Reid Harbor would be jammed with boats, and the campground would most likely be full as well, and so I was hoping Prevost might be a better option, so we headed north through John’s Pass between Stuart and Johns Island.

Thankfully we were able to find a campsite, though the best ones had been taken either by kayaking tour groups or motor boaters looking to sleep on solid ground, which meant hauling all of our gear up a steep hill and through a dense wooded forest several hundred yards from our landing site. Ironically the site was overlooking Reid Harbor, the very harbor I’d been trying to avoid in the first place, but it was late, we were tired and hungry and there was a pissed off deer out there somewhere that I had no desire to mess with. So we made camp, cooked and ate a fine dinner of tortellini and pesto and went to sleep listening to Kansas Greatest Hits emanating from the harbor below.

The next day, Saturday August 29, 2020, was cold. Cold enough that we chose to lay in our sleeping bags and read books until noon. The weather forecast was for a Small Craft Warning and and so we planned to stay off the water and have “an island day”. Our good friends Ryan and Anna know a couple who live on Stuart, Maria and Lenny, and Lenny had offered to meet up with us and show us around a bit.

Lenny took us to the top of a hill near his place where we were greeted with breathtaking views straight down Haro Strait to the south and across Boundary Pass to the west. I was reminded of something an old mariner had told me, “It’s not the end of the Earth, but you can see it from there.” Looking down at Haro strait I could see the route we would follow the next day. The plan was to paddle around Turn Point on the west end of Stuart, make a quick stop on a beach just east of the point and then swing out wide into Haro Strait to catch the currents running south. Our next stop would be on Henry Island almost seven miles away, by far our longest crossing of the trip. I told Lenny of our plan. “Cool,” he said smiling, and then added, his eyes taking in the expanse of ocean in front of us, “That’s a lot of open water.”